Vietnam’s foreign policy in a changing regional order

Analysis. Tension in the South China Sea reflects recent dynamics in the growing US-China rivalry. China’s aggressiveness, the Trump administration responses and visions of a regional order have been making headlines lately. In face of the Sino-US confrontation, Vietnam pursues a strategy of cooperation and struggle with both countries, writes UI intern Thu Le.

Publicerad: 2020-01-21

The US-China drama is visible across different channels such as the Shangri-La Dialogue and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as well as other major Asian summits. China is establishing a “community of common destiny,” a Sino-centric network of relations with peripheral nations. The United States counter-narrates with its Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy, released in 2018, where “small nations need not fear larger neighbors.”

In a maritime dispute where most relevant states are maintaining a low profile, Vietnam stands out by vocally objecting to the Chinese stance. Vietnam has objected to many of Beijing’s claims and activities in the South China Sea. Though Vietnam’s foreign policy retains elements of fluidity, being a persistent objector on the South China Sea puts the country under scrutiny.

Realism’s balance-of-power theory expects that Hanoi would align itself with Washington against Beijing, but that indeed has not happened, and will not happen unless a drastic change in domestic policy occurs. Indeed, increased diplomatic relation with both Washington and Beijing shows that Vietnam’s multidirectional foreign policy is growing even stronger in the face of a Sino-US confrontation. In 2015, Nguyen Phu Trong became the first-ever general secretary of Vietnam’s Communist Party to visit the United States and Xi Jinping visited Vietnam for the first time since becoming China’s president. Since then, Vietnam has been promoting diplomacy at both high and low levels with the US and China.

Vietnam is a strategic hedger in relations with China and the US. Though Vietnam is protecting its security interests, decisions are based on other factors as well – most notably economic interests. Overall, Vietnam wants to seek a close security relationship with the US, but not at the expense of strong economic relations with China.

Understanding Vietnam’s framework for foreign relations helps understand how Hanoi is navigating itself amidst tension and confrontation. The one-party state bases its policies on four principles: independence and self-reliance, multilateralization and diversification of external relations, struggle and cooperation, and pro-active international integration.

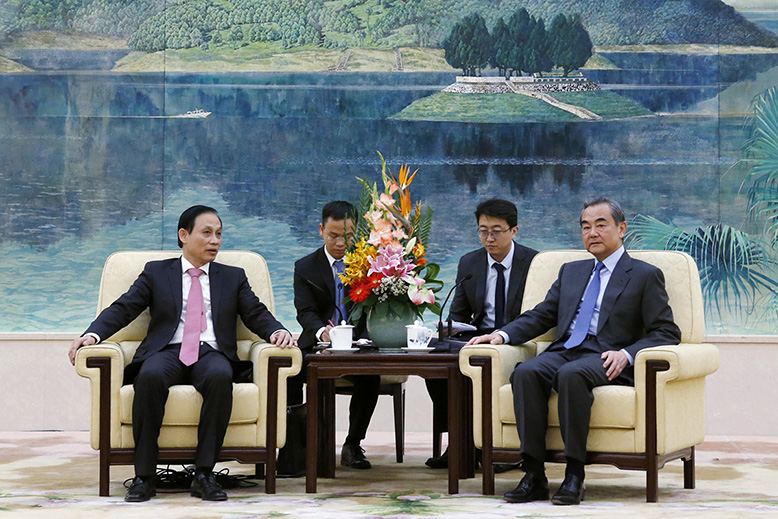

General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong ahead of his historic visit to the United States in 2015. Photo: Tran Van Minh/AP/TT

General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong ahead of his historic visit to the United States in 2015. Photo: Tran Van Minh/AP/TT

On independence and self-reliance, Vietnam has a “three nos” approach in defense: “no military alignment or alliance with any power, no military bases on Vietnamese soil, and no reliance upon another country to counter a third party.” With lessons from a history of war and isolation, Hanoi has been endorsing multilateralization and diversification of external relations since the 8th national party congress in 1996. Along with pro-active international integration, multidirectionalism allows Vietnam to have as many partners as possible to reap as many economic, political, and security benefits as possible; hence partnerships with the US, China, ASEAN countries, EU and Russia. These partnerships shield Vietnam from bullying and threats by major powers.

The strategy of cooperation and struggle are particularly reflected in Vietnam-China relations. The relations of the two neighbors have long been impacted by mutual ideology and economic interdependence, but also by overlapping maritime claims.

After a string of diplomatic deterioration since the late 1970s and the border war 1979, Vietnam and China began their full normalization of relations in 1991, but it took until 2008 before they upgraded the bilateral relations to a strategic partnership. That was later upgraded twice to reach a comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership in 2013.

They set up a Joint Steering Committee as a platform for consensus on a range of subjects. Since 2014, they have conducted an annual Border Defense Friendly Exchange. China is Vietnam’s major trading partner since 2004 and the bilateral trade is growing strong. Vietnam is also the fourth-largest recipient of Chinese foreign direct investments.

However, Hanoi’s relationship with Beijing is not without limitations and concerns. Bilateral tensions with China has primarily been caused by long-fought territorial disputes. Chinese operations in 2019 near the Vietnam-claimed Vanguard Bank had Vietnam call out China as an aggressor. A similar crisis happened in a 2014 standoff when China established an oil platform near the disputed Paracel Islands.

Vietnamese in a rally in the Philippines, protesting Chinese defiance over an international arbitration ruling on the South China Sea in 2016. Photo: Bullit Marquez/AP/TT

Vietnamese in a rally in the Philippines, protesting Chinese defiance over an international arbitration ruling on the South China Sea in 2016. Photo: Bullit Marquez/AP/TT

Given Vietnam’s asymmetrical relationship to China, the country seeks peaceful resolutions by bringing the issues to different platforms and cooperating with great powers, such as the US, to counter the influence of China.

However, though Hanoi very much appreciates Washington’s support for a less aggressive and less influential Beijing, it cannot risk its economic dependence on China by choosing China’s biggest competitor – the US. There is a pattern of hedging in Vietnam’s strategy.

Relations with the US are a tool to reduce Vietnam’s economic dependence on China and a counterbalance to China’s aggression in the South China Sea. A comprehensive US-Vietnam partnership was agreed in 2013. In 2014 and 2015, a number of high-level diplomatic visits to the US indicated a growing Vietnamese consensus that the US is an important partner. Maritime capacity building is one of the five areas of cooperation in the comprehensive partnership. The US shares a common concern with Vietnam over China’s action in the SCS.

Also, the US is the largest export market of Vietnam. In 2018, Vietnam recorded a 40-billion dollar trade surplus with the US. The US also became one of the leading sources of foreign direct investment in Vietnam, mainly from high-tech corporations. It is worth noting that in 2015, the trade surplus Vietnam enjoyed with the US almost equalled the deficit Vietnam had with China. When the US-China rivalry exploded into a trade war, Vietnam was seen as the biggest winner. China’s southern neighbor was granted investment licenses for more than 1,720 projects in the first half of 2019, up 26 percent compared to the same period the year before.

But China’s losses are not always US gains. Because Vietnam’s policy separates economic relations from security relations, tension in the South China Sea will not negatively affect the overall relationship with China. In the end, Hanoi is still largely dependent on Beijing.

USS Carl Vinson in 2018 became the first US navy aircraft carrier to visit Vietnam since the Vietnam War. Photo: Bullit Marquez/AP/TT

USS Carl Vinson in 2018 became the first US navy aircraft carrier to visit Vietnam since the Vietnam War. Photo: Bullit Marquez/AP/TT

The partnership status with the US is instructive on this point. In 2013, both countries mulled upgrading their comprehensive partnership to a strategic partnership, but Hanoi pulled back because of concerns that it would antagonize Beijing. That leaves the US a clearly less important partner than China, given that Vietnam has, in order of depth, five types of partnership: comprehensive partnerships, strategic partnerships, extensive strategic partnerships, strategic comprehensive partnerships, and comprehensive strategic cooperative partnerships.

Last year, a strategic partnership was suggested again, but Hanoi is still reluctant. Vietnamese media, under the supervision of the Communist Party, were not allowed to refer to an upgrading. The canceling of 15 defense engagement activities with the US in 2019, against the backdrop of intensifying confrontation with China, also signals Vietnamese sensitivity.

Furthermore, as Vietnam sees a more multipolar world taking shape, the party-state is worried about a perceived decline in US commitments in the region. Vietnam cannot rely on the US alone. Recently, President Donald Trump called Vietnam a currency manipulator and “the worst abuser”, and Hanoi is being threatened with punitive economic measures. Like Vietnam-China relations, US-China relations are shaped by cooperation and struggle. The US still needs to work with China on issues of convergent interests such a global financial regulations and climate change. The South China Sea could be one of the trade-offs for convergence. In a statement after the Trilateral Security Dialogue in August, the US, along with Australia and Japan, devoted three of its sixteen paragraphs to the South China Sea without singling out China by name. The attitude makes Vietnam uneasy on aligning exclusively with the US.

Though Vietnam does benefit from the strategic rivalry between the US and China, prolonged confrontation could jeopardize Vietnam’s status as a balanced hedger if it is forced to take sides. Furthermore, new dynamics can destabilize security in the region, and Vietnam would be a direct victim. The country’s objectives for peaceful co-existence and economic development would likely be harmed. However, without tension between these two powers, Vietnam might lose the protection from the US against China’s so-called bullying.

So far, the multidirectional foreign policy proves to be a solid choice. Vietnam is not likely to change the policy as long as it fits its objectives in development and security, and promotes the country’s standing in the international arena. Unless China pursues a completely aggressive policy towards Vietnam, or if the US decides to stay completely sidelined in Asia-Pacific region, Vietnam can still be a good friend to Washington without antagonizing Beijing and can still peacefully voice against China to protect its national interests.