Putin's expected election victory is also his dilemma

Interview. The opposition has been silenced and everyone knows that Vladimir Putin's ruling party “United Russia” will win the forthcoming election to the national parliament, the State Duma. Still, those in power in the Kremlin have reason to worry, says Andreas Umland, a researcher at the Center for Eastern European Studies.

Publicerad: 2021-09-12

With a pleased face President Putin entered the podium at the “United Russia” Congress on August 24 and announced that retirees, military and police would receive an extra monetary gift before the Duma election on September 17-19. The audience was also told about other major investments such as five new cities in Siberia as well as billions of rubles for emergency housing programs and for the fight against forest fires. This all implied that “United Russia” may continue as before.

The promises should be seen in light of the party's historically poor opinion ratings – between 27 and 30 percent. That is around 10 percentage points lower than before the last elections in 2016, when the party gained more than three quarters of all seats.

According to the independent Russian opinion institute Levada center, 44 percent of Russians think that the country is heading in the wrong direction. The government's efforts are ranked even lower: 51 percent give it a fail.

The government's popularity first plummeted at the end of the summer of 2018, following a decision to significantly raise the retirement age for both men and women. The Covid-19 pandemic and its effects on the already stagnant economy increased the discontent.

Decided but still uncertain

The Duma election is important for consolidating United Russia's grip on power ahead of the 2024 presidential election, when Putin may stand for another term. Ideally, it should take place without any major scandals or protests. The goal is to maintain the majority required to be able to change the constitution on their own, but that outcome is not given.

Satisfied Putin gives election promises at the United Russia party. Photo: Grigory Sysoev, Sputnik via AP / TT

Satisfied Putin gives election promises at the United Russia party. Photo: Grigory Sysoev, Sputnik via AP / TT

“This election is a challenge for Putin and his regime as popular support for United Russia has declined, yet a resounding victory of the party is supposed to happen. Although manipulation can secure the desired result, it is difficult for the regime to know in advance what degree of manipulation will be tolerated by voters,” says Andreas Umland, a researcher at the Center for Eastern European Studies and a specialist in Russian and Ukrainian politics.

“A challenging scenario for Putin and his circle would be, for instance, that there will be the same extensive protests as after the Duma elections of 2011. The dynamics of such protests are difficult to predict as the partly successful and partly abortive so-called Color Revolutions of the recent past in the post-communist space have shown. Thus, the stakes are indeed high for the regime,” says Umland.

To ensure that nothing goes wrong, the government has silenced virtually all opposition and all independent media. After the attempt to poison regime critic Alexei Navalny in the summer of 2020, opposition politicians have been harassed in various ways, arrested or felt compelled to leave the country. Since Navalny was imprisoned at the beginning of the year following a verdict that many consider to be politically motivated, his political organization and his anti-corruption foundation have been branded extremist and thus forced to close. Some leading figures around Navalny have gone into exile for fear of their safety and in order to continue operating.

Only a few candidates who can be described as critical of the regime have been granted permission to stand in the election. At the same time, it has become more difficult to monitor the election process as the voting will be spread over three days (for pandemic reasons). The independent Russian election observation organization “Golos“ (Voice) has also been restricted in its operation by being branded as a "foreign agent." This designation makes the work of NGOs that have received foreign funding more difficult. These and other restrictions related to the State Duma elections this September are also the reason why the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is not sending any observers.

“Smart Voting” – a double-edged sword

Navalny continues to fight against the regime from his cell in Punishment Camp No. 2 in Pokrov, east of Moscow. In an interview with The New York Times in August 2021, he urged Russians to go and vote according to the "Smart Voting" tactic he launched in 2018, which has since been successfully applied in a number of regional and local elections. The “Smart Voting” tactic is for oppositional citizens to vote for those alternative candidates who have the greatest chance of beating a candidate from United Russia in a given district. This is recommended even if the alternative candidate in question may not meet the voter’s expectations and belongs to one of the other three parties in the current Duma (the Communists, “Fair Russia,” or Vladimir Zhirinovskii’s ultra-nationalist party) that more or less follow the Kremlin line. The idea of this approach is to upset United Russia's grip on power.

The police grab a demonstrator with a "Vote Smart"-placard in Moscow in August. Photo: Alexander Zemlianichenko / AP / TT

The police grab a demonstrator with a "Vote Smart"-placard in Moscow in August. Photo: Alexander Zemlianichenko / AP / TT

“However, this strategy is controversial in that it will lead to a higher turnout in the elections which is positive for the regime. Moreover, it often strengthens voter support for parties that operate within the Putin regime and which are not much better than United Russia,” states Umland. “But still, the ‘Smart Voting’ strategy breaks the logic of the Russian patronal system and creates friction within the power structure and corruption networks. It is thus perhaps the smartest thing that Russian voters can do under the given circumstances. Their influence over the election will not be decisive, but the tensions created within the ruling elite may in the long run be destabilizing for Putin's regime,” foresees Umland.

New technology helps voters

Ahead of the election, the “Smart Voting” campaign has created an app that can be downloaded. In most cases, the app gives a clear message about which candidate you should vote for. It is said to be based on an algorithm that takes into account local factors such as historical voting patterns in different regions, the various parties' campaigns and other aspects.

The “Smart Voting” tactic can affect the outcome in terms of the distribution of the seats that are filled through majoritarian elections in single-member districts (see fact box). Thus, the authorities have done their best to stop the app. Threatening a fine, the state-run monitoring body Rozkomnadzor tried to force Google and Apple to remove it from its engines. When that failed, Rozkomnadzor blocked Russian voters' channels to the app.

Other methods are governmental counter-campaigns on social media with recommendations that look confusingly similar to the “Smart Voting” advice. There has also been reuse of an old dirty trick –to field in a district candidates with the same name as that of the main opposition candidate.

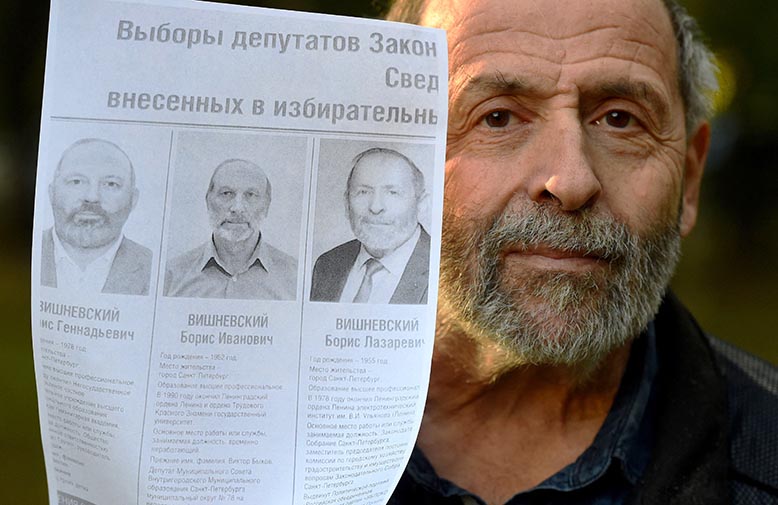

Boris Vishnevsky from the small opposition party Jabloko is trying to be re-elected to St. Petersburg's regional parliament. There are now two other candidates who have recently taken the same fore- and surname, “Boris Vishnevsky,” and who look similar to him.

Dirty trick. Opposition politician Boris Vishnevsky is being challenged in his constituency by Boris Vishnevsky and Boris Vishnevsky, who have similar hairstyles and beards. Photo: Olga Maltseva / AFP / TT

Dirty trick. Opposition politician Boris Vishnevsky is being challenged in his constituency by Boris Vishnevsky and Boris Vishnevsky, who have similar hairstyles and beards. Photo: Olga Maltseva / AFP / TT

Putin stands firm

Although Putin's ratings have fallen since peaking at 89 percent after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, he is still far more popular than his ruling party “United Russia.” About 61 percent of Russians think he does a good job as president and he can continue to present himself as the one who knows best which direction the country should choose.

“The lack of real alternatives and opposition parties is the main reason for the relatively high support for Putin, and to a lesser degree, for ‘United Russia.’ The candidates who appear as challengers are carefully selected so as to provide a theatre of democracy without threatening the power of the current ruling elite. There is also fear in the population of significant social instability in the event of a change of power, which means that many support the current regime in order to avoid upheaval,” says Andreas Umland.

“The younger generation, however, is a problem for the regime. Younger people do not watch much state TV, which is the government's most important propaganda instrument. Instead, they widely use other channels to inform themselves. They also look differently at, for example, World War II and the victory of the Soviet Union than previous generations. There is an ever-deepening gap between the generations. This is a development, to be sure, that is also noticeable in the West. In Russia, however, the cultural difference between the generations formed during the Soviet era and those who grew up thereafter is even deeper,” adds Umland.

What are Putin's chances of remaining in power in the long run?

“There is an indirect threat to the regime emanating from the democratization and liberation processes that are taking place in the post-Soviet world – especially in Ukraine and Belarus. Most Russians consider these nations to be closely related. Therefore, political instability, opposition and change in these countries have suggestive effects on the Russians. That is also one reason for Russia's manifest interest in and aggressiveness with regard to Ukraine and Belarus,” Andreas Umland emphasizes. “Finally, there is a threat of internal elite division over the future direction of the country in light of the past seven years' poor economic development. Every year with little or no growth produces more dissatisfaction within the population and elite. This could be a ticking time bomb for Putin's regime,” states Umland.